Table of Contents:

- Part 1: 1989 -1994

- Part 2: 1990 – 1998

- Part 3: 1996 – 2004

- Uplifting and Vocal

- Hard Uplifting

- Tech Trance -> Techlifting

- Part 4: 2004 – 2020

- The EDM Era

- Pushback

- Part 5 (coming soon): 2020 –

- The Underground Era

- Manifesto for the Future

Uplifting & Vocal

The era of celebrity DJs was in full swing by the mid-1990s. Up to that point, the trance scene had been centered primarily around Germany and the UK. The scene was now seeing its center of gravity shift to the Netherlands. Anthems which had been a part of trance since the hard trance days in Germany, were now becoming ubiquitous. A new style of trance was emerging.

The emerging sound combined elements of hard trance with elements of anthem house to create what would become the most commercially successful subgenre of trance. Some called it anthem trance, some called it euphoric trance. These days, most people know it as uplifting trance. It would become so popular that it practically became synonymous with trance, despite moving further away from the trance ethos over time. For clarity, we’ll refer to this style simply as uplifting.

Though uplifting is primarily a Dutch creation, its story really begins in the backyard of Alexander Shulgin, a psychopharmacologist in California. Shulgin set up a home-based laboratory on his property that would come to be known as “The Farm.” In 1976, one of the students in Shulgin’s medicinal chemistry group at San Francisco State University introduced Shulgin to MDMA. Though MDMA had been first synthesized by Merck back in 1912, it had been all but forgotten since.

The chemical piqued Shulgin’s interest, and he began working on a new synthesis method. After judicious testing on himself and his friends, he published his recipe for what would become known as Ecstasy. Ecstasy provided users with a state of prolonged euphoria, energy, connectedness, and intimacy.

Within a few years, MDMA began appearing in gay nightclubs in Dallas, Texas, often sold at the bar. The DEA estimated that Dallas residents were consuming nearly 30,000 hits of ecstasy per month and in April 1985, MDMA was classified as an emergency schedule 1.

From its start in gay clubs, ecstasy and electronic music would become forever linked. And, as with most things that start in the gay community, it didn’t stay there. It was soon seeing its popularity soar with straight people too.

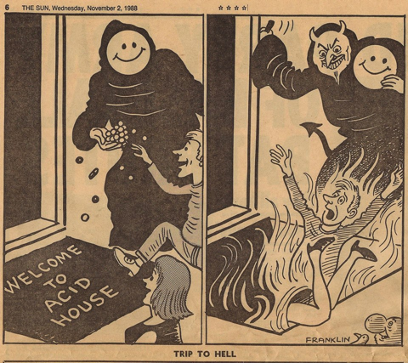

By 1988, the drug had crossed the pond which led to the “Second Summer of Love” in the UK, and Ibiza became the epicenter of the scene and this new club drug. In Ibiza, the DUI rate plummeted. Despite this, British media and tabloids began covering the rave scene in a sensationalist way, covering the rave scene’s association with ecstasy.

In newspapers around the country, outlandish and unfounded statements were fanning the flames. When the Sun’s chief medical correspondent stated in an article that ecstasy could lead to a rise in sexual assaults and that users could end up locked in mental institutions for life, moral panic set in.

In 1992, the Castlemorton Common Festival took place. 30,000 to 40,000 people partied for a week. Authorities came down hard on the revelers. Following Castlemorton, there was a push to curb illegal raves and free parties. In 1994, despite protests which ended in people being beaten and tear-gassed by police, Parliament passed a bill that updated the definition of rape to include anal rape and banned simulated child pornography. Tucked into that bill was an unrelated section that banned unlicensed gatherings of 20 or more people where there was “music,” which the statute defined as “sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.”

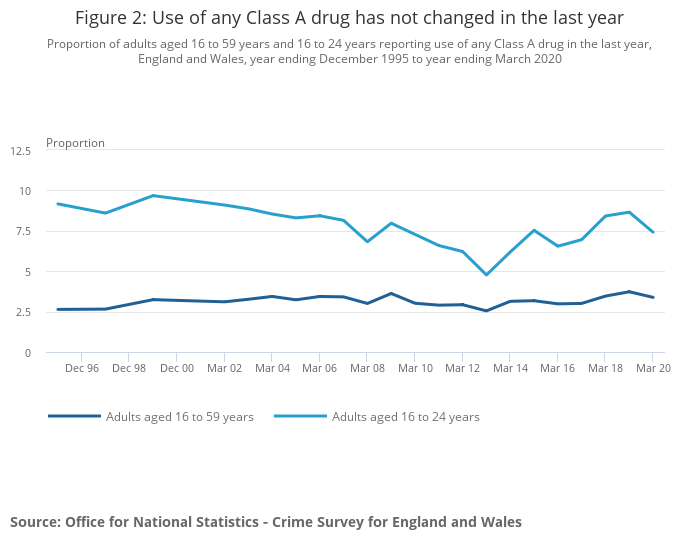

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act had the effect of pushing raves out of the underground and into clubs that could be more easily controlled–and taxed. With the scene going mainstream, MDMA became mainstream right along with it. 1995, the year after its passage was one of the most profitable years for club promoters in the UK’s history. The Act seemed to have no impact on MDMA usage.

Commercialization did impact the scene though, it warped a fundamental part of electronic music but commodified the illusion—the neon glow sticks, the outrageous outfits, and ecstasy—to a point where its consumers forgot how far they’d strayed from the counterculture identity of the scene.

Commercial success came at the price of more political and social pressure on the scene to conform to societal norms. This impacted the music and the scene. Robert Miles‘ track Children was an example of this. According to Miles, he created his hit song, Children, as a way to calm rave attendants before sending them home from events and to reduce car accident deaths. First released in January 1995, the original Balearic trance tune did not chart.

Simon Berry heard the Dream trance version of Children one night in a Miami nightclub when Joe Vanelli, played it during his set. Vanelli was the label boss of DBX Records. After hearing the track, Berry worked with Vanelli to release the Dream version as the lead single for Miles’ Dreamland album.

Dream trance was a short-lived subgenre that sprung up in Italy. Characterized by soft piano melodies and a steady 4/4 bass drum; the emphasis is on the melody. Miles did not invent dream trance, but Children is the best-known example of a genre that never veered too far from its formula.

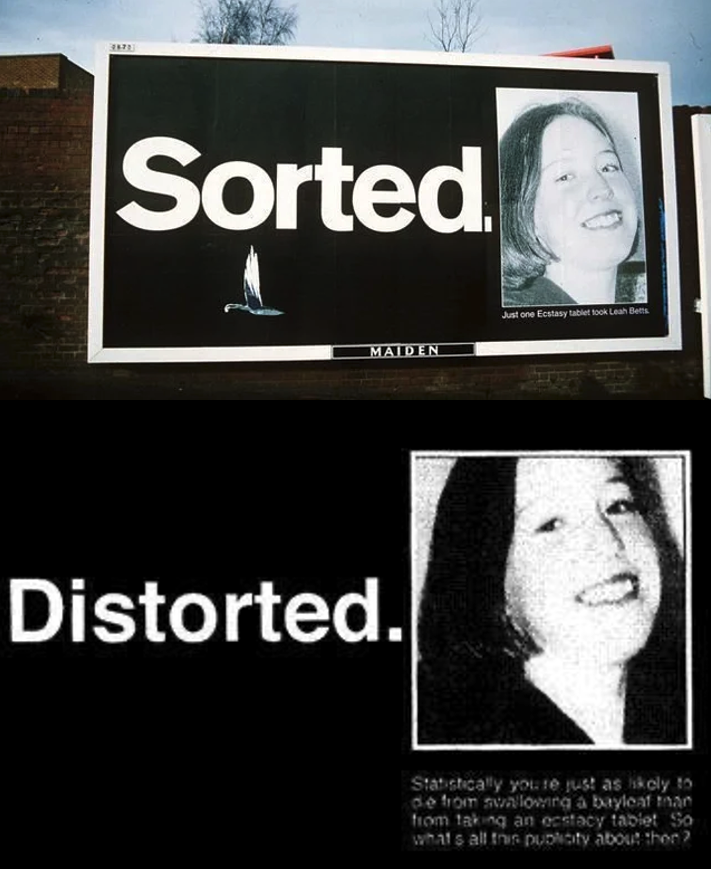

Despite the rave scene’s efforts to conform, its move into the mainstream did not insulate it entirely from criticism. The media had inexorably linked MDMA and the rave community. When a young 18-year-old named Leah Betts died after taking MDMA at home, the media coverage was extensive and highly critical of the rave scene and electronic music’s relationship with ecstasy usage, despite the fact that Leah had not taken MDMA at a rave.

Young Leah had not been the first person to die in the UK after taking MDMA. It is not clear why the story gained the type of traction that it did. Perhaps it was because of Leah’s middle-class background. Perhaps it was because her father was a former police officer, and her mother was a drug counselor. But, whatever the reason, the coverage was widespread and relentless. The family released photos of Leah hooked up to a ventilator. The photos were splashed across newspapers around the UK.

Leah’s father, Paul, would become a vocal campaigner against drug use. An advertising company representing the alcohol industry and Red Bull energy drinks put together a large ad campaign featuring a smiling image of Betts with the words “Sorted. Just one ecstasy tablet took Leah Betts.” The ads were plastered on billboards across London. The ads drew the ire of many in the music industry, including an English rock band called Chumbawamba. They produced a poster, “Distorted. Statistically, you are just as likely to die from eating a bay leaf as from an ecstasy tablet.”

Leah Betts had not died because she ate a bay leaf or an ecstasy tablet, and she hadn’t died at a rave, but facts didn’t get in the way of a good story. The media spent several weeks writing headlines like “Ecstasy pill puts party girl in a coma.” Eventually, once the facts came out, it was found that Leah’s death was the result of drinking 7 liters (about 1.8 gals) of water in less than 90 minutes because she had heard the admonishments to stay hydrated and took it too far. The excessive amount of water caused “water intoxication” which led to serious swelling of the brain, irreparably damaging it. But for the water, Leah would not have died.

The fairer articles wrote things like “Ecstasy girl may have drunk too much water.” But many continued to write that it was the ecstasy tablet that killed her. Fairness was not the top priority as the media played up the emotional aspects of the truly heartbreaking story, nor did it stop politicians who didn’t like or understand rave culture from playing up the story to promote their agenda.

Leah’s death became a rallying cry for the media, the public, and Members of Parliament. Parliament and the media doubled down on the failed policies of the past rather than seeing her death as a call for proper drug education. Nobody took the opportunity to look at the effectiveness of criminalizing drugs.

In the midst of the media frenzy, Parliament passed the Public Entertainments Licenses (Drug Misuse) Act in 1997. Its passage meant the government now had increased authority to shut down even legally licensed venues if police suspected drug use on or near the premises. The fact that Leah had taken MDMA in the comfort of her own home escaped Parliament and much of the public.

The new law had little if any effect on ecstasy usage, which continued to go up between 1997 and 2000. While it did not curb the popularity of the drug, it did allow city governments to set sometimes cruel, often arbitrary, and completely ineffective rules that varied from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Some municipalities set rules aimed at preventing the playing of high-tempo music. Other jurisdictions targeted businesses that stayed open late. Even the existence of “chill out” areas to cool down was used by some jurisdictions as evidence of drug use on the premises, sufficient to justify shuttering a club for drug use.

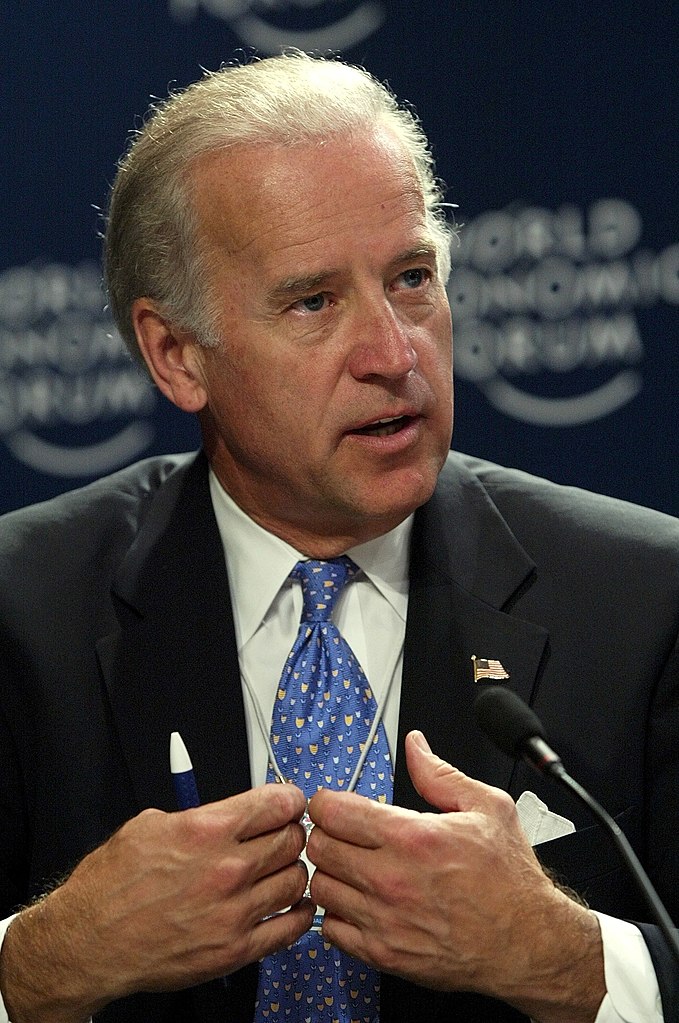

Promoters couldn’t be sure what would land them in hot water and what wouldn’t, so most opted to do nothing which might open them up to liability. It wasn’t just the UK that would see these kinds of laws passed over the next decade. In 2003, Joe Biden led the charge to pass the US Rave Act. The Act had the unfortunate (and presumably unintended) impact of discouraging rave organizers from providing medical assistance to attendants.

The RAVE Act made it easier to prosecute, fine, and imprison business owners, property owners, and rave promoters for failing to prevent drug-related offenses committed by customers, employees, tenants, or other persons on their property. When the law was first proposed, the electronic music community organized sustained opposition to the bill and it died in Congress. In April 2003 the RAVE Act renamed the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act of 2003, snuck through Congress as an attachment to the Amber Alert Bill. Despite the name change, it was still the same Act, with the same issues that had been met with such resistance by the electronic music community.

The law’s passage effectively eliminated the underground rave scene, where promoters often openly allowed and even encouraged drug use. The commodification of raves was swift. Raves became mainstream, multi-billion dollar events that attracted thousands of people. This made rave promoters paranoid. Promoters would go to great lengths to avoid looking like they were aware of drug use at their events. They stopped offering drug kits, some even stopped giving out free water which could prevent potentially fatal heatstroke.

The vagueness of the statute led many promoters to fear that precautions would incriminate them under the RAVE Act, making raves more dangerous. Before the RAVE Act, event organizers commonly offered medical and educational services for illicit drug users and partnered with harm-reduction service providers like DanceSafe. Rather than face liability, many promoters and insurers regularly insist that the Rave Act is a legal barrier to providing attendees basic harm reduction services like drug education and even free water. Most chose to avoid precautions altogether. Efforts to repeal all or part of the RAVE Act have so far been unsuccessful.

But I digress. We’re here to talk about Trance music. But, to understand the evolution of trance, you need to understand the context of the rave scene at the time. The underground rave scene was being stifled by laws and regulations aimed at doing just that. There was a growing club scene, and a business model aimed at commodifying raves into something more controllable by the government and more profitable by corporate interests. Of course, commercial interests quickly recognized the appeal of keeping up appearances. If you don’t have a robust underground scene, it’s good for business if you pretend to.

Global Underground is a label founded in 1996 by Andy Horsfield. The label would take globe-trotting superstar DJs like Sasha & Digweed, Paul Oakenfold, Carl Cox, and Solomun to exotic locations, record the sets, and then release them as part of a compilation. They are one of the first labels to place photos of the DJs on album covers.

With the rave scene becoming more mainstream, simultaneously, trance was shedding its underground roots in favor of a more formulaic, pop-oriented style of music. The concept of hypnotic music designed to entrance the listener simply wasn’t as important now that there was MDMA to provide feelings of euphoria. So, the music began to reflect the euphoric, uplifting feelings that MDMA induced. Long breakdowns and big drops replaced the gradual tension and release that had defined early Trance.

Hard trance had included breakdowns, progressive had extended them but uplifting took it to a new level, often extending breakdowns to 64 bars or more. The rhythm became less important and the music became melodically driven. Every producer wanted to create an anthem that would play at peak time and so every song became an anthem.

As the Netherlands became the forefront of the scene, Dutch producers had some advantages. The Dutch were quick to recognize the earning potential of the dance music industry. A Dutch entertainment company named ID&T began hosting a festival Mysteryland in 1993, making it the oldest electronic festival in the Netherlands. In 1996 Amsterdam Dance Event (ADE) was held for the first time. “The Woodstock of Dance” was a multi-day music conference and festival. 30 DJs performed in front of 300 delegates at the first iteration of ADE.

By the time they started hosting Trance Energy (the first festival dedicated entirely to trance), and Sensation (which would become so large it would eventually get broken into two: Sensation White and Sensation Black), they had several years of experience hosting electronic festivals. Dutch DJs had the advantage of being local to some of the biggest music events in the world. At its peak, Trance Energy was attracting over 40,000 fans to Utrecht.

The first of the Dutch DJs to find commercial success was Ferry Corsten. In 1996, Corsten released “Galaxia” and “Don’t Be Afraid” under his Moonman moniker. The two tracks are early examples of the anthemic sound that would come to dominate the genre. Corsten established his dance label Tsunami in 1997. That same year Armin van Buuren released “Blue Fear,” which was his first commercially successful track. With Armin’s success, the Dutch had established themselves as major players in the Trance scene at the time.

In 1997, Tiesto and Arny Bink formed Black Hole. From this label, Tiesto released his highly successful Magik series. Tiesto and Bink also formed the sub-labels In Trance We Trust and Songbird where they pushed music from other Dutch DJs, including Misja Helsloot, Ferry Corsten, and Armin van Buuren.

The Dutch sound was characterized by its uplifting and euphoric feeling, fast tempo, rhapsodic melodies, long breakdowns, and huge drops. With the music’s pop-adjacent sound, Tiesto and Armin’s labels effectively utilized the internet, and digital music distribution to increase the visibility of their labels’ releases.

The days of Tiesto living in Ferry’s shadow were short-lived. It was Tiesto who would see himself rise to the very top of the global scene. It didn’t hurt that he had one of the most popular female vocalists in music to help carry him into the stratosphere. By the time Tiesto released his remix of Silence by Delerium, Sarah McLachlan was a household name. The remix exploded. Structured like a pop song, the track was a powerful exhibition of Sarah McLachlan’s impeccable vocal skill.

If there were any doubts about who was leading the scene, Corsten and Tiesto’s Gouryella project quickly dispelled them. Their self-titled track, “Gouryella” was released in May 1999. It was a huge hit, as was their Remix of Binary Finary’s “1998.” Their release “Tenshi” was featured on FIFA Football 2002 and Dance Dance Revolution X2. Tiesto left the project in 2001.

Armin was also continuing to see success with releases such as Communication (1999), Exhale with System F (2001), and The Sound of Goodbye (2001). In June 2001 ID&T Radio broadcast the first episode of A State of Trance, Armin’s radio show. At first, Armin presented the show in Dutch, but when ID&T dropped the show after just over 180 episodes, he began airing the show in English to expand his audience.

The anthemic sound began to take on a more uniform sound in the late 1990s with the introduction of the Roland JP-8000. The JP-8000 was released in early 1997. It was one of several virtual analog modeling synthesizers (VA synths) that came to market around that time. The Roland JP-8000 had a feature called the supersaw oscillator whose sound would become ubiquitous in Uplifting.

Ferry Corsten’s “Out of The Blue” was one of the first hit songs to utilize the JP-8000’s supersaw oscillator. Released under his System F alias, the track was met with great enthusiasm. Corsten succeeded in creating one of the most iconic anthems of the era, and in doing so redefined Trance for a generation of Uplifting producers who attempted to copy the formula.

It wasn’t just Trance that was seeing more commercial success. Across genres, the scene was changing in one way or another. Most genres were feeling the effects of celebrity DJs. Even the Goa offshoot, Psytrance, was experiencing more global recognition, thanks to some Psytrance DJs out of Israel where the sounds of Goa were infecting the nation, and the world. Infected Mushroom and Astral Projection became internationally recognized acts.

As the millennium approached, DJs such as Armin van Buuren, Ferry Corsten, Paul Oakenfold, Paul Van Dyk, and Tiesto were spreading the anthem sound they helped popularize. The commercial, reverb-drenched sound that was playing on dance floors around the world bore little resemblance to its namesake.

In 1999 DJ Sasha released Xpander. It received the International Dance Music Award for “Best Techno/Trance 12.” The title track was featured on Pete Tong’s Essential Selection. Sasha would soon migrate to Progressive House.

In 2000, Lost Language was formed as a sublabel of Hooj Choons. Hooj had become more focused on Progressive House. In 2003 Hooj closed due to financial difficulties, leaving Lost Language independent of its former parent. Lost Language was run by Ben Lost until 2005. The goal of the label was to release quality Trance and avoid the traps of commercialism. They released music by Tilt, Solarstone, Accadia, and others. While Lost Language was trying to avoid the traps of commercialism, other labels were embracing and promoting it.

Vocal Uplifting

EMI and their sublabel, Positiva quickly recognized the appeal of vocals in Trance. The label had several hits under its belt, including B.B.E’s Seven Days And One Week (1996), Binary Finary’s “1998” (1998), and Veracocha’s “Carte Blanche.” They also began releasing music from Eurodance producers like Alice Deejay (“Better Off Alone”) and Ian Van Dahl’s “Castle In The Sky” (2000). The tracks were popular. Many fans didn’t know the difference between Trance and Eurodance, and so they were often lumped together.

It wasn’t fans who were struggling to tell them apart. The differences were diminishing. Eurodance had all the trappings of popular music that mainstream audiences were familiar with. As labels like Positiva sought to capitalize, Uplifting began to incorporate more and more of the features of Eurodance, blurring the lines. Positiva began including vocal versions alongside original mixes, even for tracks that were originally intended as instrumental. Often the vocal versions received more airplay on radio and television, becoming the only version anyone knew.

The more tracks strayed from the underground Trance sound, the more commercially successful they often became. By 2004, Trance had become a vocal genre. Perhaps no song exemplified the transition better than Motorcycle‘s As The Rush Comes. The track featured stereotypical female vocals and followed a pop song structure. It became one of the defining tracks of the early 2000s era of vocal Uplifting.

A new label was started at the beginning of the new millennium called Anjunabeats. Originally started as a duo of the same name by Paavo Siljamäki and Jono Grant. Their first single, Volume 1 was picked up by DJs such as Pete Tong, Paul Van Dyk, and Judge Jules. Paavo and Jono would soon meet Tony McGuiness, who recruited them to help him produce a remix of “Home” by Chakra (same producers as Lustral, Space Brothers, and Ascension). When Tony McGuiness, a music executive, joined they began working under the name Above & Beyond.

The remix reached #1 in the club charts. Thanks to their success, and Tony’s connections, the trio was soon receiving additional requests from Tony’s colleagues for remixes of their client artists. One of those artists was Madonna. Above & Beyond remixed “What It Feels Like For A Girl.” When Madonna heard it, she liked it so much that she decided to use the remix for the music video.

Soon Above & Beyond was playing stages alongside Tiesto and Ferry Corsten. Using the internet to their advantage, they began building a fanbase that would become one of the largest and most loyal in electronic music history, “Anjunafamily.”

In 2002 Above & Beyond released “Far From In Love” which became a huge vocal hit. They also released highly successful vocal tracks under their alias Oceanlab. Those tracks included “Clear Blue Water,” “Satellite,” “Sirens of the Sea,” and “On A Good Day,” among others. Nearly every release was a hit.

Above & Beyond went on to release their first album, Tri-State, which was a hit. They performed at events like Gatecrasher. As their popularity grew, the influence of their label grew. They signed artists like Oliver Smith, Tinlicker, Andrew Bayer, Ilan Bluestone, Mat Zo, and many others who would help the label become one of the most well-known electronic labels.

Andrew Bayer would be especially influential in the later Anjuna sound. As the popularity of commercial Uplifting faded, Anjunabeats updated their sound. Some called it “Trance 2.0.” There was little if anything Trance about it.

The new Anjuna sound of the 2010s was a slower, chunkier Big Room festival sound. Spearheaded by producers like Andrew Bayer, who was substantially contributing to tracks for Above & Beyond, as well as releases under his name, this sound kept Above & Beyond and the Anjuna stable of artists headlining events in the United States and around the world.

By the time Above & Beyond released their second album, Group Therapy, they had dispensed much of the Trance sound in their music and were promoting a more big room EDM sound. Despite the change of sound, the label managed to remain true to its ethos. Anjunafamily prides itself on its reputation as one of the kindest, most loyal fanbases in electronic music.

In 2006, a radio show called Future Sound of Egypt (FSOE) was launched by Egyptian DJs and producers, Aly & Fila. In 2009 they founded FSOE Recordings. With releases from artists such as Dan Stone, Factor B, M.I.K.E. Push, Stoneface & Terminal, and The Thrillseekers, FSOE has become one of the biggest labels in Uplifting. The label also spawned FSOE UV, a Progressive sublabel run by Paul Thomas, and FSOE Clandestine, which focuses primarily on Techlifting and Hard Uplifting.

Hard Uplifting

In the late 1990s, a new style emerged that featured an Uplifting construction, but with a more aggressive sound, compressed kick drums, and exaggerated basslines. At the time, this new Uplifting offshoot was called Hard Trance. Because this disregarded that Hard Trance already existed in a different form, it created confusion. For the sake of clarity, and accuracy in genre-fication, we’ll refer to this as Hard Uplifting.

Like Uplifting, Hard Uplifting still has some Trance elements. Hard Uplifting is distinguishable by its excessive use of white noise, and its more exaggerated kick drum. It features the type of anthem sounds that the Dutch made popular with Uplifting. Long breakdowns and big drops were common. Supersaws which had become an essential part of Uplifting was also carried over into Hard Uplifting. While producers from around the world contributed, it was nonetheless primarily a Dutch style.

Like with Uplifting, anthems with screeching synths were nearly ubiquitous. As this louder, more abrasive sound continued to evolve, it would spawn Hardstyle. The Hard Dance scene was very popular for a while, and as a result, ID&T decided to expand Sensation which had started as an Uplifting event. They created Sensation Black which focused on hard dance styles such as Hard Uplifting and Hardstyle. Sensation then became Sensation White, which was the Uplifting-focused event.

Tech Trance → Techlifting

For many, the direction of the Trance scene was troubling. Uplifting and Hard Uplifting were so different from Trance as it was originally conceived, that they might as well have been entirely new genres, rather than subgenres of Trance. Each style still contained some Trance elements, but with an entirely different ethos and sound. Rather than hypnotic, the tracks focused on creating a euphoric feeling.

Seeing that Uplifting and Hard Uplifting were supplanting Trance, some producers began trying to go in a new direction, which was back towards a Trance sound that shed the commercialism, anthems, and pop influences. The result was Tech Trance. At first, Tech Trance was easily distinguishable from Uplifting and Hard Uplifting.

Many credit Oliver Lieb for the formation of Tech Trance. Examples of the early Tech Trance subgenre include Ecano (Oliver Lieb), Run; Breeder The Chain; A Travel In Time by Trance[]Control. It didn’t take long before the influences of Uplifting began to creep into Tech Trance as well.

Soon Tech Trance became nearly indistinguishable from Hard Uplifting. The introduction of anthems, vocals, and pop song structure was swift. Ultimately, Tech Trance failed to return Trance to its original ethos or to have much of an impact at all. Today Tech Trance sounds similar to, if not exactly like Hard Uplifting. In our opinion, a more apt name for the subgenre would be Techlifting.

To be continued…