Part I

“Study the past if you would define the future.”

Confucius

We often get asked, “What is trance music?” or “Why is it called Trance?” We hope to answer some of that here. Trance is a genre of electronic music that emerged in the late 1980s in Frankfurt, Germany, and quickly spread throughout Europe. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the genre had moved away from its underground roots. Largely adopting pop song structure and vocals, the genre experienced mainstream success on a scale that no other electronic genre had yet experienced. Below is an in-depth history of trance music from its earliest days to the present.

The Beginning

In the early 1980s, Andreas Tomalla worked in a record store in Frankfurt’s central station called “Music City.” To make it easier for customers to find electronic records in the store, Tomalla decided to put all the electronic records on the same shelf under the name “techno”.

“I actually filed everything under techno. And people liked it! They came into the store and knew where to find electronic music,” Tomalla said. At the time, the selection was small and there was little need to distinguish between genres. New Order, Depeche Mode, Kraftwerk, DAF, Heaven 17, Front 242, and many early electronic pioneers lived on those shelves.

Perhaps more than anyone at the time Tomalla, or Talla 2XLC as he became known, shaped the music scene in Frankfurt. As the 1980s continued, the collection of techno on Talla’s techno shelf was growing. House and acid house music from Chicago, electronic body music, and experimental electronic like Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, as well as techno from Detroit. In Frankfurt at the time, EBM was the most popular genre of electronic music.

EBM is a danceable industrial music genre that emerged in Europe in the 1980s. Combining a steady 4/4 drumbeat, with driving, repetitive bass lines, and often shouted vocals. Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream deeply influenced EBM producers. Kraftwerk’s Ralf Hutter coined the phrase “electronic body music” in 1977. DAF began calling their music “body music” in the 1980s. Nitzer Ebb and Front 242 followed DAF and helped to define the genre.

In 1984, Talla started Technoclub. Technoclub was likely the first club event to play exclusively electronic music. Held at various clubs around Frankfurt, Technoclub quickly became the hottest scene for EBM, though it existed primarily as an underground scene for suburban kids.

The cool or trendy clubs in Frankfurt in the early 1980s were Vogue and Plastik, and they played the popular music of the day: disco, soul, and funk. When Sven Vath became a DJ at Vogue, their sound began to change. They started playing EBM, the music that Talla and his Technoclub had been playing all along. In Berlin by the late 1980s, it was Acid House that was taking over dance floors.

Acid House was an emerging form of House music originating in Chicago thanks to a monophonic analog synthesizer by Roland. Released in 1981, the TB-303 Bass-line was intended for use as a bass accompaniment for rock bands. Approximately 10,000 units were produced before the TB-303 was discontinued due to poor sales.

The 303 seemed destined for failure until House music producers in Chicago fished them out of bargain bins. Instead of using the 303s to produce bass lines, the producers would push play and tinker with the nobs. When used in this way, the equipment produced a distinctive squelching sound that became known as acid.

In 1987, Phuture released a track utilizing this sound, titled Acid Tracks. The song clocked in at 12 minutes and 26 seconds long. Featuring a 4/4 beat, and a single looping line with constant twisting of the nobs to create the acid sound. Acid Tracks took Chicago dancefloors by storm and quickly spread to the UK and the rest of Europe.

Upon arrival in Berlin, Acid House found a home at UFO Club. Founded in 1988, UFO Club was not styled like a club. Down in the basement of an old building, the was accessible by climbing down a ladder. The ceilings were low, only around 6 ft, and usually had cobwebs hanging from them. The tiny club barely had enough space for 100 people at full capacity.

UFO Club was often so crowded that visitors would bump into the walls. For hours they would dance, until, finally exhausted, they would go home covered in dust. Though small in size, this little club would play an outsized role in helping establish Berlin as a center for electronic dance music; it hosted the afterparty for the very first Love Parade.

The Love Parade was a parade that had an estimated 150 participants who took to the streets of Berlin on July 1, 1989. Created as a political demonstration for peace and understanding, through love and music, the parade would become a massive celebration of electronic music and youth culture.

Few could have predicted that within months, the Berlin Wall would be coming down. Cut off from the rest of Germany, conditions in West Berlin were difficult. There was very little industry and jobs were scarce. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, West Berlin had become a haven for misfits, queer people, hippies, and artists. A thriving underground scene formed around them that included experimental music, avant-garde art, political activism, and a vibrant club scene.

Across the Wall, in East Berlin things were different. Life was marked by a mix of political repression and social control. The government tightly controlled education, media, and culture. Censorship was widespread. Until the Wall came down, records were hard to come by. The only music publisher was a state-run label. This didn’t stop East Berliners from getting exposure to electronic music. They would listen as West Berlin radio waves were beamed over the Wall. Some West Berlin broadcasters even played their tunes so that they could be fully recorded. The surging popularity of cassette tapes made it easier to record music.

Those in East Berlin who secretly tuned in to West Berlin radio were also hearing about what was happening in the West Berlin clubs. The Wall separating them just fed the hunger for East Berliners to experience it for themselves. Clubbing in East Berlin was a very different experience from what they were hearing about in West Berlin.

Nightlife in East Berlin was subject to strict government control. In East Berlin, clubbing was more of a social outing where people went to talk and get drunk. Music was usually provided by live bands or state-approved cassettes. Despite the strict social control in East Germany, young people were drawn to hip-hop culture, fashion, and dance, including breakdancing.

An underground culture emerged that practiced breakdancing in secret in abandoned buildings or hidden corners of public parks to avoid attracting attention. This culture of community and experimentation fed the hunger of many East Berliners to experience West Berlin-style clubbing. They wouldn’t have to wait long.

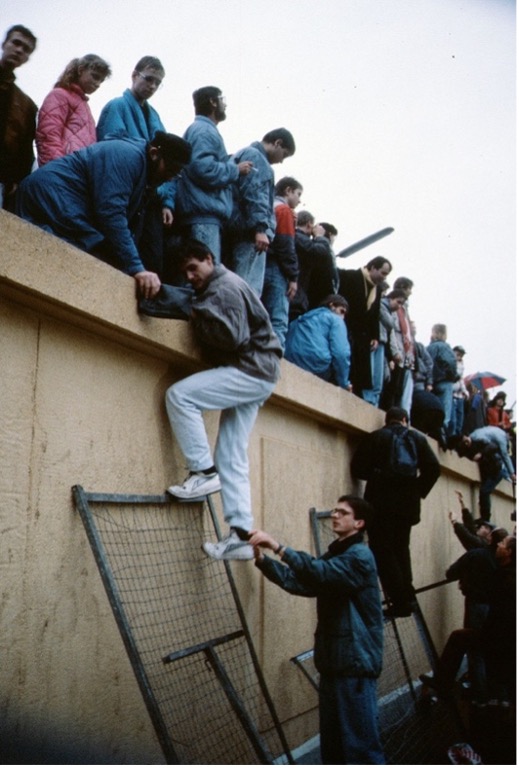

On Thursday, November 9, 1989, the Iron Curtain fell. The East German government announced that its citizens could freely travel to the West. People on both sides flocked to the checkpoints. West Germans greeted East Germans with champagne and flowers as the East Germans crossed into West Germany, some for the first time. Many climbed onto the wall in celebration. For many of those celebrating, the Wall had been up for their entire life.

As East Berliners made their way into West Berlin, they were often easy to spot. Wearing stone-washed denim and looking out of place, they caused long lines at McDonald’s and the sex shops in West Berlin. The East Berliners overwhelmed music stores looking for Western records and musical equipment. It was a new era of freedom. The celebration was euphoric. Parties seemed to pop up anywhere and everywhere. For some East Berliners, the first thing they wanted to do was go to the clubs.

Some East Berliners went straight to clubs such as UFO Club. The East Berliners had never seen anything like it. Trippy-painted fabrics covered the walls of the club. Smoke and lights filled the air. A DJ stood in one corner and mixed for hours.

The experience was novel and foreign for the East Berliners who were used to East Berlin discos which were held in state-run clubs. The music was limited to approved genres and artists and DJs often stopped the music to make announcements. At the UFO Club, the music was the focus.

Reintegration wasn’t without conflict. Many took their time adjusting to a new reality. There were those on both sides that believed their respective side was better. Yet, little by little, and day by day reunification happened in the acid house-infused underground. Some East Berliners began visiting UFO Club and other West Berlin clubs every week.

The soundtrack of Reunification was electronic. The music gave unity of purpose to people who were looking toward the future. Some felt so strongly about the music that they gave up their jobs to take part in the movement. They opened record stores, and rave wear stores. They booked, promoted, or hosted parties; or they became a DJ, or music producer. Many saw themselves as missionaries with an obligation to push the scene forward.

The scene they were pushing forward was egalitarian. In the beginning, most producers didn’t DJ, and most DJs didn’t produce. Many were concerned that producers as DJs would lead to celebrity DJs, a development that they did not want. The DJ was part of the party, not its focus. There was no need for stars, nor was there any room for them.

Reality disappeared into the swirl of sounds. Faceless artists, with ever-changing project names dissolved in the circuitry of the synth and drum machine. Dancers lost themselves in the 0s and 1s of the binary code. Combined, they transformed abandoned, decaying buildings into magical wonderlands.

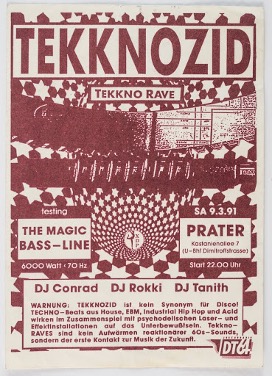

One of the residents of East Berlin that crossed over was Wolfram Neugebauer. Wolfram, or Wolle XDP as he became known, organized Tekknozid raves, the first raves. The parties were conceived with the goal of ecstatic dance on a mass scale. There were no bars, no tables, and no seating. They wanted to get as far away from the classic disco atmosphere as possible.

As Wolle would describe it: “I wanted people to experience a collective sensation through trance, and find a way back to a humanity that they can’t find otherwise.” To achieve this, Wolle used faintly-glowing lighting effects, individually controlled strobes that matched the rhythm of the music, and a four-point sound system with additional bass installations to create a hypnotic atmosphere.

The Tekknozid concept worked well. Participants danced for hours in a trance-like state. Around the dance floor, huge stages were set up. Dedicated dancers with light sticks danced on the stages to provide additional rhythmic lighting effects. Guest DJs such as Energy 52, and Talla 2XLC, as well as resident DJs, DJ Roland 138 BPM, and Tanith provided the music.

In those days, the sound of electronic music was constantly evolving. As the scene in Germany continued to evolve, it became clear that two schools of thought were emerging. There was the Frankfurt School with its tribal, hypnotic Trance sound that was evolving from EBM and influenced by Acid House. At the same time, the Berlin school was developing which was evolving from the Techno from Detroit.

Techno was born in Detroit, but no club scene had developed to accommodate the sound. Neglected at home, the Detroit producers exported their music to Europe where it found a home in Berlin. The sound started to gain traction. Detroit techno featured the unyielding sound of machinery, it was mechanical and precise, but with soul and house influences.

Germany’s sense of ownership over techno makes sense. They had influenced it. Juan Atkins and other techno originators have long credited the raw machine sounds, abrasive rhythms, and driving bass lines of the German band Kraftwerk as inspiration for techno.

As Berlin adopted techno as its own, German producers brought their take to the Detroit sound. The Berlin sound removed any soul and House influences and embraced the mechanical nature of Techno.

In Frankfurt, producers were no less inspired by Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Jean Michel-Jarre, and others, but where Berlin was going mechanical and abrasive, Frankfurt was going towards tribal and hypnotic. In Frankfurt, they were trying to induce a trance state with their music, emphasizing spacey and atmospheric themes.

Throughout Germany, raves and illegal clubs featured DJs playing various emerging styles of music. Drawn to the freedom that raves represented, many people were drawn to the sounds. Some people were looking for an escape; for others, raving provided purpose and meaning. But, whatever their reasons, many believed that they could make a better world. They danced to make it so.

Original Trance

“It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.”

Oscar Wilde, Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray

In Terminal 1 at Frankfurt Airport there was a club called Dorian Gray. Dorian Gray was named after Oscar Wilde’s only novel, “Picture of Dorian Gray”. The club’s namesake is a story of the young hedonistic Dorian Gray who sweeps aside societal ideas of morality. Liberated, Dorian sets out in pursuit of beauty and pleasure.

The story’s homosexual undertones and “immorality” caused such a backlash that it led Wilde to write a preface in response. In the preface, he asserted that art is art for art’s sake, its meaning is subjective, always striving to become a matter of perception.

Wilde argued that all art aspires to the condition of music. As the most abstract form of art, music is unbothered by morals or intelligence, it can take the listener on a journey of their choosing, wherever their imagination can take them. Wilde’s preface is a manifesto for the artist’s right to creative liberty. In Frankfurt, in a club named after this piece of art, trance was born.

Dorian Gray was one of the largest nightclubs in Germany at the time. Modeled after Studio 54 in New York, the club was flat and made of concrete, like a parking garage. A Richard Long Soundsystem sat along the Club’s neon-painted walls. The sound could be felt as much as it could be heard. The place demanded excellence, and DJs came to deliver.

The doors to Dorian Gray had first opened in 1978. In its infancy, the club’s music largely consisted of disco, funk, and soul. When Sven Vath came along, he changed up the sound. EBM groups such as Front 242 and Nitzer Ebb started coming to play.

Dorian Gray had a 24-hour license which meant you could stay there all night and into the next day. The crowds could be intense. As time a more hypnotic sound began to emerge as resident DJs Sven Vath, Torsten Fenslau, and DJ Dag tried to create a condition inside the club where people were en-tranced by the sounds.

Sven Vath had traveled to India and come back from the beaches of Goa, armed with the knowledge of what DJs were doing to induce a trance state using psychedelic rock and other sounds. This deeply influenced Vath’s music. From this, something began to develop in Frankfurt.

Dorian Gray and Omen became the hotbed of this new Frankfurt sound. Vath, Fenslau, and Dag, with their affection for trancey dance sound, along with other producers in Frankfurt, began to craft music that would help them create this condition on the dance floor.

In 1988, Fenslau released The Dream under the alias Out of The Ordinary. The Dream (Acid Mix) was an EBM track that borrowed heavily from Acid House. In 1989, he released another track with his group Abfahrt titled Alone (It’s Me) which moved the sound still further away from EBM. Some believe that this was the first Trance track.

Also in 1989, Fenslau’s Abfahrt label released “Play It Again” under his alias Out Of The Ordinary. While the A-side was more typical of EBM, the B-side track “Play It Again (Why Don’t You Try This Side)” solidified Fenslau’s role as one of the earliest creators of Trance. The same year that “Play It Again” was released, Fenslau’s label released a record from another upstart Frankfurt producer named Oliver Lieb, under the alias Force Legato.

In addition to Fenslau and Vath, there was DJ Dag Lerner. DJ Dag met Rolf Ellmer (Jam of Jam & Spoon) in 1990, and the two decided to work together on a project. Their first release came in 1991, under the alias Dance 2 Trance. It contained two tracks: “Dance 2 Trance” and “We Came In Peace”. Their biggest commercial success was Power of American Natives, released in 1992.

Some other early examples of the emerging genre were Hypnopedia by Hypnopedia, You Can Run (Hypnotic mix) by 3 Times 6, Running by Tyrell Corp (another project that included Fenslau), Cosmic Love by Resistance D (1991). As DJs from German cities traveled with their posses, they carried their regional sounds with them, which led to an explosion of new experimental genres.

With an explosion of new genres, techno as a catchall phrase for everything electronic didn’t work anymore. The more mechanical sounds of Techno were too dissimilar from the funk and groove of House music. Neither was descriptive of the hypnotic, tribal sound that was spreading from Frankfurt.

In the 1980s the word “trance” had been increasingly used to describe electronic music. Tangerine Dream’s Klaus Schultz released En=Trance, and The KLF released What Time Is Love, part of their “Pure Trance” series. KLF would later release Last Train To Trancentral with the words “Pure Trance” on the sleeve of the record. It was likely DJ Dag that first gave the “Frankfurt sound” the trance name.

Initially, trance didn’t have many rules. The music was defined by the hypnotic feel of the music, not time signature, beat pattern, or tempo. For music catalogers who frequently didn’t understand trance, categorizing the music could be challenging.

Websites such as Discogs frequently mislabeled trance tracks as techno or even house because it wasn’t clear to them whether a track was just trancey techno, deep house, or ambient.

Despite the lack of rules, trance tracks did share some traits. A steady 4/4 beat with driving and clean repetitive bass lines. Interweaving elements were layered over the continuous beat, creating spacy atmospheres; always with the goal of producing a psychological experience for the listener.

Tracks were usually long; 6-10 minutes was common. Long intros and outros allowed the DJ to mix a seamless trance set into what seemed like one continuous song. To maintain the entrancing effect, changes in mood were subtle and vocals were uncommon, though some early tracks included EBM-style vocals.

Critically, trance shirked the verse-chorus structure of pop music, following a progressive or cyclical structure featuring longer and more gradual builds, with an emphasis on the journey rather than the destination. Compared to other electronic genres at the time, trance was melodic. Still, the melodies were not over-the-top. The music was minimal but relatable.

At the time that trance originated, Frankfurt was Germany’s business and financial center–more cosmopolitan and sophisticated than Berlin and the music reflected this. It was more refined, less raw than the Berlin sound.

At Frankfurt clubs, the crowds were diverse and a touch avant-guard. They were a mix of gay and straight. People often painted their nails and would dress colorfully—nobody batted an eye. As a Berliner during that time described them: the people of Frankfurt were “freaks with a tribal touch.”

Frankfurt saw an explosion of output of trance thanks in large part to the formation of two of the most influential trance labels of the era. In 1990, Sven Vath created Eye Q, and its more underground sub-label Harthouse.

Musically, Eye Q took a softer approach to trance with releases such as Cygnus X’s “The Orange Theme,” Zyon’s “No Fate,” “Vernon’s Wonderland” by Vernon, “Café Del Mar” by Energy 52, and many more. Meanwhile, Harthouse was releasing tracks such as “Quicksand” by Spicelab, and “Acperience 1” by Hardfloor, a darker take on trance.

In the early era of trance, one of the most influential producers was Oliver Lieb. Lieb was prolific, releasing under aliases such as L.S.G., Spicelab, The Ambush, Ecano, and others. He was also part of groups such as Force Legato (with Fenslau), and Paragliders. All told, Lieb has produced more than 250 singles and albums.

Another prolific Frankfurt producer was Peter Kuhlmann. In 1992, Kuhlman started Fax +49-69/450464, another early trance label created as an outlet for his own works and his collaborations with other German electronic producers. The label soon expanded to ambient and downtempo which became its predominant focus in later years.

Kuhlmann released music under the name Pete Namlook, as well as several other aliases, including Sequential, 4Voice, and Deltraxx, among others. 4Voice was a project with Maik Maurice Diehl.

Maik Diehl had another trance project known as Resistance D with yet another Frankfurt producer named Pascalis Dardoufas. Dardoufas produced under the alias Pascal F.E.O.S. Dardoufas released tracks on both Eye Q and Harthouse, but eventually started his own label, Planet Vision (PV) which released music until the early 2000s.

Trance quickly spread out from Frankfurt. Labels such as ESP Record (Netherlands), Rising High Records (UK) and its sublabel Ascension, as well as Harthouse UK emerged. In Berlin, a Brit named Mark Reeder started his own trance label.

Reeder had moved to Berlin in 1978. By the time he founded Masterminded For Success (MFS) Records in 1990, Reeder was well-established in the Berlin music scene. He originally created MFS to give a platform to East Berlin producers. He quickly ran into a problem–he couldn’t find any East European artists to promote.

To start MFS signed West Berliners such as Paul Browse and Mijk van Dijk. Quickly signing others, the label released a compilation in 1992 to showcase its producers. In what was likely the first trance compilation, Tranceformed From Beyond, the compilation, mixed by Mijk van Dijk and Cosmic Baby, was a DJ-style continuous mix of releases by MFS producers such as Humate, Voov, Cosmic Baby and others. One of the others was young Paul van Dyk.

Paul van Dyk’s had his first club gig at Tresor which was the successor to UFO Club. Where UFO Club had been the home of acid house in Berlin; Tresor would become the home of Berlin techno.

Located inside an old vault, the club was a room within a room. Tresor’s reinforced concrete walls provided little air exchange. When the fog machines were turned on, it became nearly impossible to see. Most of the visitors were so familiar with the club that they could find their way around anyway.

Illegal events in abandoned buildings were common. Often parties would pop up and disappear quickly. Some, however, had a lasting impact on Berlin. One such party called Planet, which started as an illegal party in an abandoned building near the city center. It soon got shut down and by the Summer of 1992, they were looking for a new location.

On the banks of the Spree, they found a former soap factory that became Planet’s new home. The building came with some amenities. Someone had forgotten to shut off the power to the abandoned factory.

The sound system was forceful. Allegedly, the pressure of the bass would lift the roof off the walls of the dilapidated building. The interior of the club was maze-like. Half-walls surrounded the dance floor and created passageways inside the building.

Planet wasn’t popular at first. The club’s location made getting there a trek. But, it eventually took off in the gay and fetish community. People would come to the club wearing gas masks and rubber gloves for fisting. Planet’s many places to sneak away and play likely contributed to its increased popularity

Visitors could often be found everywhere except the dancefloor–some off finding places to play and some simply trying to escape the club’s notorious heat. Many would go lay outside on the concrete. There was also a pool on the premises where some would swim–and occasionally skinny-dip.

Inside the clubs, the scene was growing. Berlin DJs were becoming idolized. With younger DJs feeling they had something to prove, it was common for DJs to play only B-Side tracks the crowd wouldn’t know. They believed if they were good, they could win over the crowd with B-sides.

Paul van Dyk was an exception. He liked to play hits that the crowd would know. He wanted the crowd to like him and they did. Fellow DJs were not nearly as impressed and accused him of being a bit of a “hit-slut.”

Regardless of what his fellow DJs thought, Paul van Dyk had a reputation for being hard-working. He was also known to be charming and persistent when he wanted something. Using his charm, he convinced Cosmic Baby to collaborate on a project called Visions of Shiva.

For their first single, van Dyk composed the piano sequence and provided feedback, but he mostly watched in wonder, learning what he could as Cosmic Baby built everything around that sequence. The resulting track, “Perfect Day” was released in 1992 and quickly became popular within the scene.

Frankfurt’s trance and Berlin’s techno had come up together, but techno in Europe was moving towards what Werner Vollert called, “aesthetic liminal experiences with music.” Pushing techno as close to the boundary between where music ends and noise begins as possible while maintaining its danceability.

The techno scene began to experiment with Gabber. The techno ethos was very different from trance. Techno producers didn’t want the listener to get lost in the music, they wanted them to listen and understand. The techno and trance scenes continued to diverge throughout the early 1990s.

Tresor closed in temporarily in 1992, leaving the techno scene without a place to go. One day while hunting for a new Tekknozid location, Wolle XDP and Ralf Regitz found a place. The building was a former bunker turned foodstuff storage facility. Some of the rooms on the ground floor were still full of shredded coconut, raisins, and candied orange peel.

Massive in scale, around 38,750 square feet, and unheated. It had a 7 ft. ceiling, too low for commercial use. Bunker attracted a young, often criminal crowd with a Nazi element. The Bunker crowd did not go to Planet, which they thought was too soft and too gay and took an “us” vs. “them” attitude towards people who went to Planet.

As was common, within a year Planet had closed. But by April 1993, the Planet crew opened E-Werk. E-Werk had a successful, well-attended opening, but the crowds soon dwindled. Friday nights were especially dead, as many people went to Tresor.

When Jurgen Cramer began hosting his Dubmission parties at E-Werk, Friday nights improved. According to Mark Reeder, without the Dubmission parties, the MFS artists would have had nowhere to play in Berlin. Though Tresor had re-opened it was going in a stylistically different direction.

For several years, Dubmission was Kid Paul and Paul van Dyk. Dubmission consistently drew a crowd. Kid Paul would go on to produce the Trance hit “Café del Mar” as Energy 52. E-Werk soon became the place to go.

The E-Werk crowds were younger and gayer than the Tresor crowd, consequently there was much more sex at E-Werk. It was an atmosphere of benevolent consent. Sometimes people fucked on the dancefloor. Not everyone took part in the, but if you saw someone eating pussy or sucking dick, there was no judgment. It was an escape from everyday life.

Trance flourished in this nascent rave scene in Germany in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but it wouldn’t stay there for long. The hypnotic, underground sounds of Trance would soon spread to the UK and throughout Europe, expanding and evolving along the way. But, as it grew and evolved it would eventually lose sight of its original purpose. Its history would be forgotten, its story rewritten.